Michelangelo Bergonzi

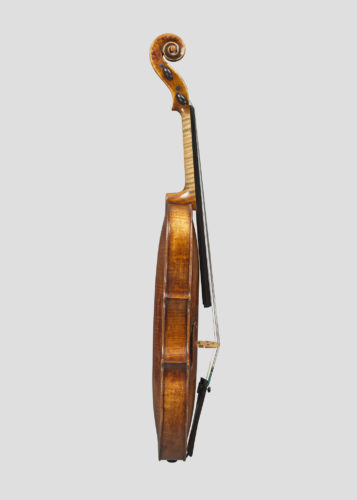

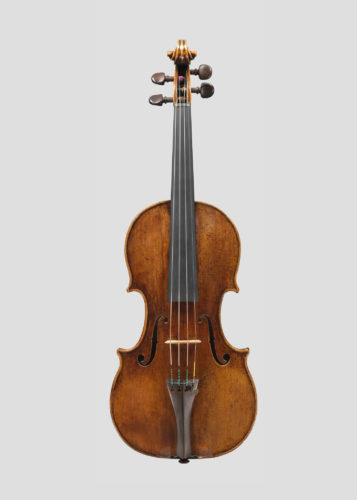

Violin made by Michelangelo Bergonzi in 1744 in Cremona, Italy. Anders Kjellberg Nilsson plays on this instrument.

If anyone can be thought of as the successor to the great Guarneri del Gesu in Cremona, it would have to be Michele Angelo Bergonzi.

Unfortunately, Bergonzi’s life was little longer than del Gesu’s own: he died in 1758, aged only 37, a mere fourteen years after Guarneri himself died in 1744. Little time to capitalise on what reputation Guarneri, or for that matter Cremona itself, still retained.

Michele Angelo was the son of Carlo, the more famous and more prolific maker of the family, with whom he moved into the Stradivari workshop in 1745, following the deaths of Antonio and his two violin making sons, Francesco and Omobono. The origins of the Bergonzi family and their place in the Cremona violin tradition is not fully resolved. Striking stylistic connections can be made with the Rugeris, which are reinforced by evidence of other local links between the families. Carlo’s work is very strongly in the Stradivarian style, and he was the natural candidate to take up the vacancy in the Stradivari shop and the Cremonese hierarchy. He lived only two more years, however, dying in 1747.

Michele Angelo in many ways closes the circle of the four great and distinguished Cremona ateliers, Amati, Rugeri, Guarneri and Stradivari. Although tightly interconnected, each had its own style and technical approach. The Guarneri family were firmly linked to the Amati in a direct line of apprenticeship. But Stradivari and Rugeri have distinct motifs and methods; the Bergonzi fit perfectly between the two. In the last years of the classical age of Cremonese violin making, the Bergonzis were the last upholders of the tradition, and fused the two ideas of the methodical perfectionism of Amati on the one side, and the improvisatory freedom of the Guarneri on the other.

The violin by Michele Angelo Bergonzi perfectly sums up the state of affairs in mid-18th century Cremona. No longer able to exercise a monopoly on violin making throughout Europe, with the rise of workshops all over Italy, in Venice, Naples and Rome, and even north of the Alps, and without the guiding hand of the maestro Antonio Stradivari, he was able to explore many alternative ideas, which may have seemed highly radical at the time.

The violin is made on the ‘B’ violin form of Stradivari, dated 1692 and still preserved in the Museo del Violino in Cremona, yet it exhibits distinctive characteristics of Stradivari, Guarneri, and Bergonzi himself. Made in the same year as the Dextra Foundation’s own Guarneri del Gesu, 1744, it provides a fascinating comparison. Indeed for many years, the 1744 del Gesu was identified as a Michele Angelo Bergonzi, such is the stylistic closeness. No Guarneri was ever made on a Stradivari mould, however.

Michele Angelo had some consistent ideas of his own- the relatively high, rounded arching contrasts with the very low, flattened arch of del Gesu’s late work. The varnish is fascinating also- it has closer links with that used in Venice, at his time still thriving as a centre of violin making. Its thick, clotted appearance, rich in pigment and soft oils, is almost impossible to imitate, and is rarely seen in this excellent degree of preservation. His scroll is developed from his father Carlo’s distinctive form with widely projecting eyes and slender windings, yet is freely carved like those of del Gesu. The soundholes are a similar cross-pollination of Guarneri and Bergonzi styles, steeply angled and widely-cut, yet with finely pointed wings. The materials used are interesting too: the back is of native Italian maple known as ‘oppio’, recognisable from the regular, narrow figure, tight grain structure and dark colour. This wood was used by most of the great Cremonese makers, including Stradivari himself, and while it may have been a cheaper option than the imported and extravagantly figured maple more usually associated with great instruments, its natural density may also have appealed to luthiers for tonal reasons. The ribs and scroll are made from unmatched wood, largely quite plain, and probably brought together within the workshop. At least one other Michael Angelo Bergonzi violin is known with a back, like that of Dextra Musica’s own 1744 del Gesu, of beechwood, possibly the most common and inexpensive hardwood available. No doubt cost was an issue in their wood selection, a reflection of the sad economic decline that Cremonese violin making experienced in the mid-eighteenth century. For the sound though, there is no substitute for the fine, straight-grained mountain spruce that forms the front of this violin, and no alternative was ever used or sought by the great makers of Cremona. Michele Angelo Bergonzi was the last of them, often overlooked in the histories, but abundantly exhibiting the definitive qualities of craftsmanship and individuality, and the unique breadth and nobility of sound that binds them all together.

Anders Kjellberg Nilsson

Anders Kjellberg Nilsson, (b. 1983), is one of Norway’s most active violinists. He has performed as soloist with all of Norway’s symphony orchestras and he frequently performs as a chamber musician and ensemble leader. He serves as 1st concertmaster with the Norwegian Radio Orchestra. (Photo by: Ingrid Halvorsen)